Overview

This English article "On Durga, Siva and Kali in Their Exoteric Aspects: A Criticism on Max Muller" appeared in three parts in The Dawn, Vol.2. No. 5, 6 and 8, September/October/December, 1901. This was a revised and shorter version of the Ṭhākura’s earlier essay entitled ‘The Hindu Idols’ that he wrote in response to the Anti-Hindu article published in the magazine of the Christian Tract Society in 1899. It would seem that this article was discontinued in The Dawn.

PART 1

The late Professor Max Muller in one part of his book “Anthropological Religion” deals with the origins of the Hindu deities Durga and Siva, and tries to establish that they are “importations from non-Brahmanic neighbours, possibly conquerors, or as adaptations of popular and vulgar deities by proselytising Brahmans;” for he holds that “neither Durga nor Siva can be looked upon as natural developments, nor even as mere conceptions of Vedic deities.” In my present paper I will try to adapt myself to the standard set up by Max Muller and look at the deities mentioned from the point of view of Max Muller’s ‘conceptions’ or ‘developments’ and see whether from this exoteric standpoint, we could not discover their origins in the Vedas. The exoteric treatment of a deity consists in treating him or her as symbolising or allegorising something is us or without us; in looking at him as a representation, not as an independent reality. In an age of scientific materialism, when most thinkers start from the conception that man is ‘matter’ fist and ‘intelligence’ afterwards, ie. is only a deprived product; that, in fact, his intelligence is not primary but is evolved through a peculiar combination of material atoms and molecules, and as such is destined to disappear with a re-arrangement of the molecules, on physical dissolution; in this age of materialism, we say, it would be the height of absurdity to claim for a deity like Durga, Siva or Kali, the character of Intelligences, supreme or of any other order whatsoever. With most thinkers of the present age, God Himself is at best a conception and is tainted with the vice of anthropomorphism. When man himself is recognised in essence only as matter, or at best a development of matter, the existence of immaterial beings, higher intelligences, or deities that are essentially spiritual, i.e. higher consciousnesses – the idea of the existence of such beings, we say, must be necessarily at a discount. When man will have begun to recognise that he is spirit first and matter afterwards, and that the spiritual element is the only element that is ever-permanent in him – that in fact, he is the Atma or self of the Hindu sages, immortal, omniscient, etc., clothed in impermanent garments which are so many impediments to his realising himself in his infinite spirituality, he would be in a position to recognise God as the Reality, and not merely as a conception, not owing His existence to us. My point is that it is ‘useless in the present state of our ideas, when man himself (albeit his rationality and emotions and will-power) is regarded only as a derived product of atoms, and God Himself as but the product of a product, a conception due to man – it is useless, we say, in the present stage of our ideas, when the notion of independent, permanent intelligence in sentient human beings is hardly recognised – to start any discussion as to whether the Hindu deities, Durga, Siva or Kali are intelligences, spiritual essences, independent realities, or whether they are mere conceptions. Therefore assuming, but not admitting, that they are mere conceptions or developments, we join issue with Prof. Max Muller and seek to establish that starting even from his standpoint that the deities in question are anthropomorphic, he is in error in supposing that their origins do not lie in the Vedas, “that they are inexplicable except as importations from non-Brahmanic neighbours, possibly conqueror, as importations of popular and vulgar deities by proselytising Brahmans.” When the Vedic deities themselves are recognised as unrealities, not essences, intelligences, independent consciousnesses, the tracing of the deities, Durga, Siva and Kali to their Vedic origins would not evidently, in the eye of the foreign Orientalist, establish their claim to be recognised as true deities, ie. realities. But still to the Hindu who recognises the independent existence of spiritual essences, higher consciousnesses; who recognises in himself an “Infinite spirit wantoning in endless being,” and not merely “an animal having a body, every organ merely performing its natural functions,” and who looks upon the Vedas as his highest authority and upon Vedic deities as realities and not mere subjective conceptions i.e. representations of outward realities even an exoteric presentment of the subject such as would be implied by the tracing of the deities Durga, Siva and Kali to their Vedic origins would be a clear objective gain. But let it be once more said that we are here not discussing the question, whether Durga, Siva and Kali are realities, or intelligences; or whether they are mere conceptions due to man, but hat, assuming, as Max Muller does (but not admitting) that they are such conceptions – whether they are Vedic or non-Vedic and non-Aryan in their origin.

Mr.Max Muller’s position will be very clearly understood from the following quotation from his book, “Anthropological Religion.”

There is such a decidedly non-Vedic spirit in the conception of Durga and her consort Siva that I feel inclined to trace it to some independent source. A goddess with four arms, or ten arms, with flowing hair, riding on a lion, followed by hideous attendants, could hardly have been the natural outcome either of Rodasi, the wife of Rudra, and of the Maruts, or even of the terrible flames of Agni, Kali, and Karali. The process to which Durga and Siva owe their present character must, I believe, he explained in a different way. It was probably the same process with which Sir Alfred Lyall and others have made us acquainted as going on in India even at the present time. When some outlying, half-savage tribes are admitted to a certain status in the social system of “the Brahmans, they are often told that their own gods are really the same as certain Brahmanic gods, so that the two coalesce and form a new incongruous mixture. Many years ago I suspected something like this in the curious process by which even in Vedic times the ancient gods, the Ribhus, had been assigned to the Rathakaras, literally the chariot-makers, a not quite Brahmanic class, under a chief called Bribu. If we suppose that some half-barbarous race brought their own god and goddess with them, while settling in the Brahmanised parts of India, and that after a time they forced their way into the Brahmanical society, we could then more easily understand that the Brahmanic priests, in admitting them to certain social privileges and offering them their partial services, would at the same time have grafted their deities on some of the minor Vedic deities.

Traces of a foreign, possibly of a Northern or North-eastern Durga, may still be discovered in some of her names, such as Haimavati, coming from the snow-mountains; Parvati, the mountaineer; Kerati, belonging to the Keratas, a race living in the mountains east of Hindustan. One of her best-known names, Chandi explained as violent, savage, belongs to an indigenous vernacular rather than to Sanskrit. Chanda and Munda, the latter possibly meant for the Munda tribes, are represented as demons conquered by the goddess, and she is said to have received, from her victory over them, the name of Cha-munda. Possibly Chandala, the name of one of the lowest castes, may be connected with Chanda, supposing that, like Munda, it was originally the name of a half-savage race. Even in so late a work as the Harivamsa, v. 3274, we read that Durga was worshipped by wild races, such as Sabaras, Varvaras, and Pulindas. Nay even Sarva, another name of Siva, and Sarva and Sarvani, names of Durga, may be interpreted as names of a low caste (see Sarvari, a low-caste woman, a devotee of Rama). If then Chandi was originally the goddess of some savage mountaineers who had invaded central India, the Brahmans might easily have grafted her on Durga, an epithet of Ratri, the night, or on Durga, as a possible feminine of Agni (havya-vahanl), who carries men across all obstacles (durga), or on Kali and Karali, names of Agni’s flames, or Rodasi, the wife of the Maruts or Rudra. This goddess is called vishita-stuka, with dishevelled locks, and Chandi also is famous for her wild hair (kesini). In the same way her consort, whatever his original name might have been, would, as a lord of mountaineers, have readily been identified with Rudra, the father of the Maruts, or storm-winds, dwelling in the mountains (giristha, Rv. VHL 94, 12, &c.), or with Agni, whether, in one of his terrible, or in one of his kind or friendly forms (siva tanuh, Satarudriya, 3). In his case, no doubt, the character of the prototypes on which he was grafted, whether Rudra or Agni, was more strongly marked, and absorbed therefore more of his native complexion, than in the case of Durga, his wife. But the nature of Siva’s exploits and the savage features of his worship can hardly leave any doubt that he too was of foreign origin. It should be remembered also that Rudra and Agni, though they were identified by later Brahman authors, were in their origin two quite distinct concepts *. I hold therefore that neither Durga nor Siva can be looked upon as natural developments, not even as mere corruptions, of Vedic deities. They seem inexplicable except as importations from non-Brahmanic neighbours, possibly conquerors, or as adaptations of popular and vulgar deities by proselytising Brahmans. But even this would not suffice to account for all the elements which went towards forming such a goddess as we see Durga to be in the epic and Pauranic literature of India. If she was originally the goddess of mountaineers, and grafted on such Vedic deities as Ratri, Kali, Rodasi, Nirriti, one does not see yet how she would have become the representative of the highest divine wisdom. The North, no doubt, was often looked upon as the home of the ancient sages, and, as early as the time of the Kena-upanishad, the knowledge of the true Brahma is embodied in a being called Uma Haimavati. She is also called Ambika, mother, Parvati, living in the mountains, and her husband Uma-pati is identified with Rudra (Taitt. Ar. 18) Having given Prof. Max-Muller’s view of the case we proceed to give ours. Let us ‘hope that from a comparison of arguments put forth, the reader will not find it difficult to come to a very definite conclusion. We will divide our arguments under the following heads: —

PART I. THE PRIMARY STAGES

(1) Durga as a Vedic conception.

(2) The Vedic Altar developed into Durga.

(3) Professor Max-Muller’s error and the non-scientific character of his treatment of the subject and the attendant practical mischief at the hands of Christian Missionaries.

PART II. THE DEVELOPMENTAL STAGES

(4) Development of Sati into Uma.

(5) Development Uma into Ambica.

(6) Development of Ambica into Durga.

(7) Durga as the representative of the Highest Divine Wisdom.

(8) Durga’s non-Aryan Names explained.

PART III. COLLATERAL RELATIONS

(9) True Nature of Siva.

(10) Kali as a Popular Deity.

(11) Kali as Humanity and Revelation.

(12) Kali as Philosophy and Love.

(13) Kali as a Sacrificial Deity.

(14) Kali as the world’s grand theatre of a demonaic beginning and a godly end.

(1) DURGA, A VEDIC CONCEPTION

For the original conception of Durga, I beg to cite 3-27-9 Rigveda, which is as follows:

oṁ dhiyā cakre vareṇyo bhutānāṁ garbhamā dadhe dakṣasya pitaraṁ tanā

“The daughter of Daksha embraces Agni (the fire) that exists in everything, that protects as a father, and that is adorable for its works.”

In Vedic times, the Sacrificial Altar was termed the daughter of Daksha, probably from the reason of the saint’s having performed a good many sacrifices. The fact that the Sacrificial Altar contains fire, or that the daughter of Daksha embraces Agni, is the very germ of the conception that Durga has for her consort Siva, who is none other than Agni (the fire), the term Rudra having been applied to both. The Pauranik statement that Sati, the daughter of Daksha, was married to Siva may be traced in its esoteric aspect to the above Rik, being either an illustration of it or an exposition of the inseparability of the altar from the fire, or of the means from the end.

(2) THE SACRIFICIAL ALTAR DEVELOPED INTO DURGA

As to the development of the Sacrificial Altar into Durga, we must remember that there was a time in the annals of ancient India, when the Rishis had to put out their sacrificial fire. They then performed no rites and made no offerings to the Fire, but they seem to have preserved the Altar, for it is said in the Vedas.

oṁ jyotiṣmatīm āditim dhārāyat-kṣitiṁ svarvatim (1-136-3, Rigveda)

“This Altar is all-brilliant, all-perfect and good-looking, and is the way to Heaven.”

The Rishis therefore preserved the Altar, before which they sat, and were absorbed in deep meditation. Now when a revival took place, it was necessary that offerings should be made to the Fire. And the Rishis instead of kindling the fire again, placed upon the Altar, upon the daughter of Daksha, and image of yellow colour to represent the Fire and called it Habya-Vahani, after the name of Agni, who was so called for his capacity for conveying the sacrificial offerings to the gods. This image is our Durga, her ten hands representing the ten directions of the Altar. The existence of a number of minor deities with her also proves without a shadow of doubt that Durga is a full representation of a Vedic Sacrifice. Her Saraswati is the knowledge of the Vedas incarnate. Her Lakshmi represents the wealth needed for the performance of a Sacrifice. Kartikeya, the warrior, preserves the Sacrifice, while Ganesa begins it, his four hands representing the Hota, the Ritwik, the Purohita and the Yajamana elements of the Vedic sacrifice. Furthermore we have

oṁ vipājasya śośucanā bādhasva dviṣo rakṣaso amīvāḥ (3-15-1 Rigveda)

(‘You, brilliant with your lustre, destroy our enemies, destroy such Rakshasas as are free from diseases.’)

Vedic mantras like the above, necessarily place the turbulent Asura, and a group of fierce animals under the subjugation of the great Goddess of Fire. Another very striking proof of Durga having been the Agni of the Vedas, is that when we worship Her, we are to invoke Her first by the following hymn of the Sama-Veda.

oṁ a agna āyāhi vītaye gṛṇāno havyadātaye Ini hotā satsi barhiṣi II

“Thou come, O Fire, for we welcome Thee to receive these oblations, be seated on the spread-out Kusa, and welcome the gods on our behalf.”

(3) PROFESSOR MAX MULLER’S ERROR AND THE NON-SCIENTIFIC TREATMENT OF THE SUBJECT: ATTENDANT PRACTICAL MISCHIEF AT THE HANDS OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONARIES

Thus, I have clearly established that Durga is essentially Vedic and exclusively Aryan; whereas. Max Muller, if he had not missed or ignored the Rik which I have already quoted (3-37-9, Bigveda) would have been at once convinced of Durga existing in Vedic times as eth Sacrificial Altar. He would then have been spared the necessity of trying to find a solution of Her origin in Ratri, Rodasi, or other Vedic deities. He would then have not lost the opportunity of identifying Sati, the Pauranik daughter of Daksha, that as was married to Siva with the Sacrificial Altar, that is the Vedic daughter of Daksha that embraced Agni. As it is, having failed to trace Durga and Siva to their proper sources, he could only devise an a priori explanation of the facts, thus; “If Chandi was originally the goddess of some savage mountaineers, the Brahmans might easily hove grafted her on Durga, an epithet of Ratri.” That this explanation is purely guess-work would be evident when proceeding with our arguments we establish the different stages in the process of development of the Vedic Sacrificial Altar into the final aspect of Durga. In the meantime, it is essential to note that Prof. Max-Muller himself acknowledges that his explanation of Durga’s non-Aryan origin is not satisfactory, as not sufficing to account for all the elements which went to form such a goddess as we sec Durga to be in the Epic and Pauranik literature of India. Says he, “If” (as he supposes) “she was originally the goddess of mountaineers and grafted on such Vedic deities as Ratri, Kali, Rodasi, Nirreti, one does not see yet how she would have become the representative of the hightest divine wisdom.” So, then, on his own admission, the explanation which he offers, being a priori in its nature takes account only of certain facts, and leaves out others not less important. I hold, therefore, that Max Muller’s theory being admittedly incomplete and, therefore, unsatisfactory must make room for another which is complete and satisfactory. The fact of the matter is that in tiding archaic religious institutions to their origins, foreign orientalists suffer from an inalienable vice which incapacitates them from looking at them from an historical point of view and treating them according to strict historical methods. The vice we refer to is very well expressed in the words of Sir Henry Sumner Maine. “They carefully observed the institutions of their own ages and civilisation and those of other ages and civilisations with which they had some degree of intellectual sympathy; but when they turned their attention to archaic states of society which exhibited much superficial distance from their own, they uniformly ceased to observe and began guessing. The phenomena which early societies present us are not easy at first to understand; but the difficulty of grappling with them arises from their strangeness and uncouthness not from their number and complexity,” (Ancient Law, 119-120). Mr. Max Muller’s is one such guess-work as is distinctly traceable to “the strangeness and uncouthness” of the particular phenomena with which he has had to deal. He is, it seems, simply frightened at the sight of “a goddess like Durga with four arms, or ten arms, with flowing hair, riding on a lion followed by hideous attendants” (I am quoting his own language). The uncouthness and strangeness of the picture before him suggested to him at once the hypothesis that Durga was of non-Aryan origin, was an “importation from non-Brahmanic neighbours, possibly conquerors, or an adaptation of popular and, vulgar deities by proselytising Brahmans.” And having hit upon the ‘savage’ theory of Durga, he finds many other things besides her ‘savage’ form to support the theory; e.g,. her many ‘savage’ names and of her connexion with a ‘savage’ consort, “the lord of mountaineers,” “the nature of whose exploits and the savage features of whose worship could hardly leave any doubt that he too was of foreign origin.” This ‘savage’ theory might have at least been plausible but for the fact that it could not account for “Durga as the representative of the Highest Divine Wisdom.” While Professor Max Muller has sought to establish the ‘savage’ theory of Durga’s origin, we have in turn sought under the leadership of that great champion of the application of historical method in the treatment of archaic institutions. Sir H. S. Maine, — to bring out the psychological conditions under which he, a modern civilised foreigner and orientalist, is compelled to propound what he calls his scientific theories which are however, at best a priori guesses, conjectures, suppositions etc. But the mischief which such theories do, apart from their appearing as well-established truths and so vitiating scientific thought, go further and become, indeed, formidable when they are used as weapons in the hands of bigoted proselytising believers in a foreign religion. For such theories give ample scope to such believers to hurl anathemas against their heathen brethren and to wound their religious susceptibilities, however much such anathemas may find their ultimate explanation in the foreign believer’s difficulty in understanding heathen ideas and institutions—“difficulty,” to use the language of Sir Henry Maine, “arising from their strangeness and uncouthness” on account of the foreign believer having no “intellectual sympathy” with them. That the mischief of indulging in learned guess-work in matters relating to the religious beliefs of a devoted subject people may assume gigantic proportions would be evident from the following quotations from a pamphlet (second edition 3000 copies) published anonymously in January, 1899, by the Christian Tract Book Society at 23, Chowringhee, Calcutta, and appearing under the misleading title of “Prof. Max Muller on Durga.” The quotations given are only illustrative, not exhaustive. Says the Christian tract-writer, “What infatuation possesses Hindu English educated, to cling to this non-Aryan Demon? To draw the attention of a human being to her and say, ‘Behold your Mother, your heavenly Mother’ would be to insult him and make him explain ‘Is your servant a dog to own such a mother?’ The giving of worship of Durga is worse than to take the Queen off her throne and set a scullion in her place. It is like setting the worst character in Newgate Jail in her place. For a person to pretend to come from one’s native character and to carry a portrait of one’s mother thence (a mother never seen by the child) and to present the portrait of a grinning ourang-outang and say ‘Lo, your mother.’ is not so very grossly insulting to a human being as to present to him an image of Durga or Kali and say to him ‘Lo, your God, your spiritual Mother.’” After this unmeasured language of praise given to heathen brothers and subject peoples, the anonymous writer-prophet pronounces his benedictions. The time is coining when the wolf and the lamb shall feed together and the lion shall eat straw like an ox. Surely the millenium a near at hand.” Professor Max Muller was a man of culture and devoted to the cause of truth; and notwithstanding his error in discovering the genesis of Durga nowhere uses any language of outrageous invective; but he is always sympathetic, even where he is most in opposition. But the case is quite different with those Christian Missionaries who using language such as we have quoted disgrace Christianity and the name of a Christian missionary. For ecclesiastic bigotry, selfishness, and fanaticism masking themselves under the dignified title of righteous indignation and superiority could alone be held accounting for the above language of unmeasured vilification. Bigotry and selfishness are opposed to all true culture; and the man of true culture alone is able to appreciate the fact that men and peoples and races differ constitutionally not only in primary conceptions* of God, man and the universe; but that further, (and this is more important still) that holding possibly the same essential sentiments, they may through racial peculiarities or evolutionary conditions find themselves committed to particular modes of expressing, objectifying and realising the self-same sentiments. So that what the sight of the cross evokes in the breast of the true Christian is evoked by other symbols in the heart of the true-born Hindu; while also what the sight of the (to the, Christian most unsightly) image of goddess Kali, evokes in the Hindu’s breast the idea’ of tenderness as well as of sternness, of motherly care as well as of the most unrelenting justice (which others miscall savage cruelty) may well be excited by other symbols of Christian religion. It is he barbarian, a synonym for the man who is most uncultured and therefore, most unsympathetic, who is unable to look into the depth of things and realise the true significance of varying symbols and images used by different peoples. And one of the most essential qualifications of a teacher of a foreign religion to Indians would be to possess this breadth of culture which would save him from the clutches of the Satan in him, would save him from an overmastering sense of egotism, and superiority born of such egotism and which would not ’make the name of the “Prince of Peace” whom he would profess to follow and whose teaching he offers to others, stink in the nostrils of all thoughtful, cultured men.

PART 2 (October edition)

We have done with the two primary stages as we have termed them treating first (1) Durga. as a Vedic conception and secondly treating of the connexion between the Vedic Altar and Durga. We have proposed only to present Durga in Her exoteric aspect; for it is from that view alone that Prof. Max Muller has treated Her and has denied Her a Vedic origin. We now proceed in this Part (Part II.) with what we have termed the Developmental Stages, divided under the following heads: —

(a) Development of Sati into Uma.

(b) Development of Uma into Ambica.

(c) Development of Ambica into Durga.

(d) Durga as the “Representation of the Highest Divine Wisdom.

(e) Durga’s Names; their explanation.

In our previous article on this subject we said that this explanation of Durga by Prof. Max Muller is pure guess-work would be evident when proceeding with our arguments we establish the different stages in the process of the development of the Vedic Sacrificial Altar into the final aspect of Durga.” And this we proceed now to do.

PART II. THE DEVELOPMENTAL STAGE

(a) The development of Sati into Uma.

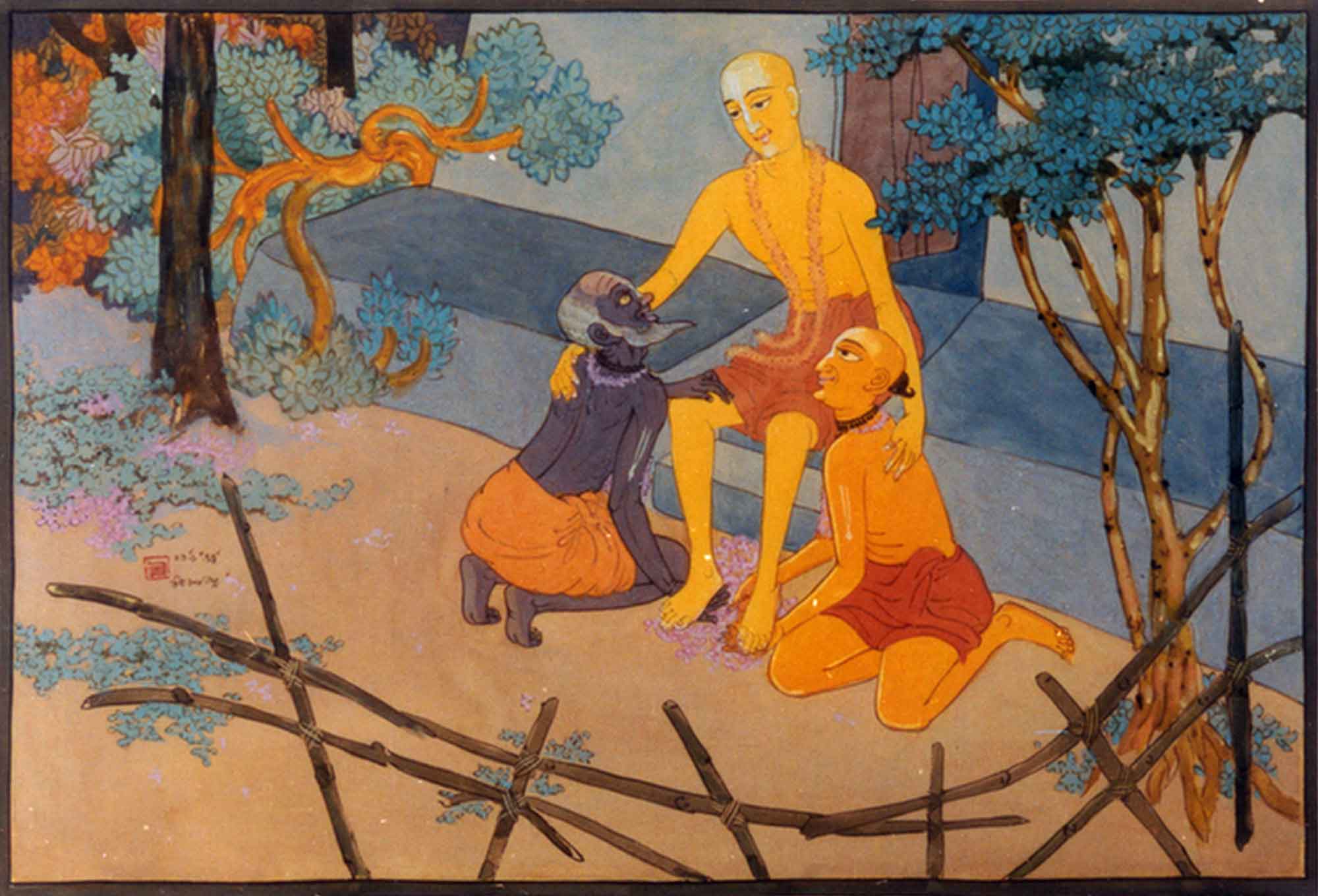

The Puranas say that Sati, the daughter of Daksha, died on account of her husband Siva being insulted by her father, and that she was again born as Uma, the daughter of Himalaya, and married to Siva for a second time.

Such sayings as these, which are generally put aside by the European scholars, as productions of a highly tropical imagination are of the utmost importance for the purposes of the present inquiry. For Sati being identified with the Vedic Altar, and Uma being identified with Sati, there can be no doubt about Durga having been exclusively a Vedic conception. Now, the Pauranik statements may be judged from three different view-points; they are either fictitious, or real, or allegorical. Now, they cannot be fictitious, for they deal with Daksha, Sati, the daughter of Daksha, Rudra, Siva, Uma and Ambica, as characters or conceptions that occur in the Vedas. We may next take them as real; and say that Sati was born as Uma in a subsequent birth which is the Hindu believer’s creed; but as this necessarily involves a question of the transmigration of souls, and calls for something like positive proof as to the metempsychosis of Sati into the person of Uma, we may leave it alone to suit the point of view of modern cultivated reader’s beliefs. He will, therefore, have no objection to treating the Pauranik statements, as allegorical or symbolical. Thus, be bill have no objection to the Hallowing explanation of the Pauranik statement. When the Purana says that Sati, the daughter of Daksha, died on account of her husband being insulted by her father, the modern western reader may take it that it was intended to be conveyed that when the Rishis put out their sacrificial fire, the altar fell fast into disuse. And he may further take it that in saying that Sati, the daughter of Daksha, was born again as Uma, the daughter of Himalaya, the Purana probably meant that a revival of the Vedic sacrifices took place somewhere in the Northern Districts. And the foreign Orientalist will be further fortified in this view if he remembers that the name Uma itself reflects a great lightupon the subject The idea of “no more meditation” is what is conveyed by the word, Uma, Says Kalidasa,

umeti mātrā tapase niṣiddhā

paścādumākhyāṁ sumukhī jagāma

(Being forbidden by her mother to meditate, she was afterwards called Uma.)

And “no more of meditation” implies probably a revival of sacrificial practices. And this revival, as we have already said, was not to rekindle the fire, but to make an image to represent the Fire.

Nor this is all. The above sloka furnishes an instance of transferred epithet; so that divested of the figure, it means that the Rishis were forbidden to meditate by a motherly spirit, whom they called Uma.

(b) The Development of Uma into Ambica

The change was not, however, abruptly made. Considerable time seems to have elapsed before Uma, the spirit prohibiting meditation and enforcing sacrifice, could be personified in Durga. We see mention of Uma in Kena-Upanishad as a splendid female being seen in the sky, whom the Rishis held to be Brahman or the Supreme Being, as will appear from the following extract.

sa tasminn evākāśe striyam ājagāma bahu-śobhamānāṁ umāṁ

haimavatīṁ täm sā brahmeti hovāca tato haiva vidāñcakāra brahmeti

“Then he (Indra) came across a splendid female in the sky known as Uma Haimavati, and said that she was Brahman; therefore, he knew she was Brahman.”

Thus, we see that Uma, though mere the Sacrificial Altar in her previous existence, was fast rising into a feminine god-head during the revival, being no longer the mere Altar, both the Altar and the Fire combined, as is clearly shewn by the following extract from the Yajurveda.

eṣa te rudrabhāgaḥ saha svasāmbikayā taṁ juṣasva svāhā

‘Oh Rudra, enjoy this your share (of oblations) with your sister, Ambica.’

During the time of Yajurveda, Uma originally the wife of, or an under-deity to, Rudra, was growing under the name of Ambica to be his sister, or rising to an equal importance, and partaking of the sacrificial offerings with the great God of Fire.

Thus we see that the ‘terrible flames’ of Agni that prevented Prof. Max Muller from identifying Durga with Agni were during the revival fast changing into the sober lustre of Ambica, tender as a mother, loving as a girl, revealing as it were, the propriety of a feminine mediation between man and God.

As to the definite form of Durga, the following Gayatri of the Taittariya Aranyaka has, in my humble opinion, contributed to it more than all the rest.

oṁ kātyāyanāya vidmahe kanyā kumārī dhīmahi Itanno durgāḥ pracodayāt II

“We invoke Durga, whom Katyayana saw in the shape of an unmarried girl, who sends us understanding.”

Under the influence of the above Gayatri, there seem to have arisen two classes of worshippers, one worshipping unmarried girls, and the other worshipping an image of the same denomination.

PART 3

PART II. The Developmental Stages.

In our last article on the subject we dwelt at some length on the two earlier stages, — namely (a) the development of Sati into Uma, and (b) of Uma into Ambica. Wo are now concerned with the third and fourth stages, namely, the Development of Ambica into Durga’ and of Durga as the “Representative” in Max Muller’s words “of the Highest Divine Wisdom.”

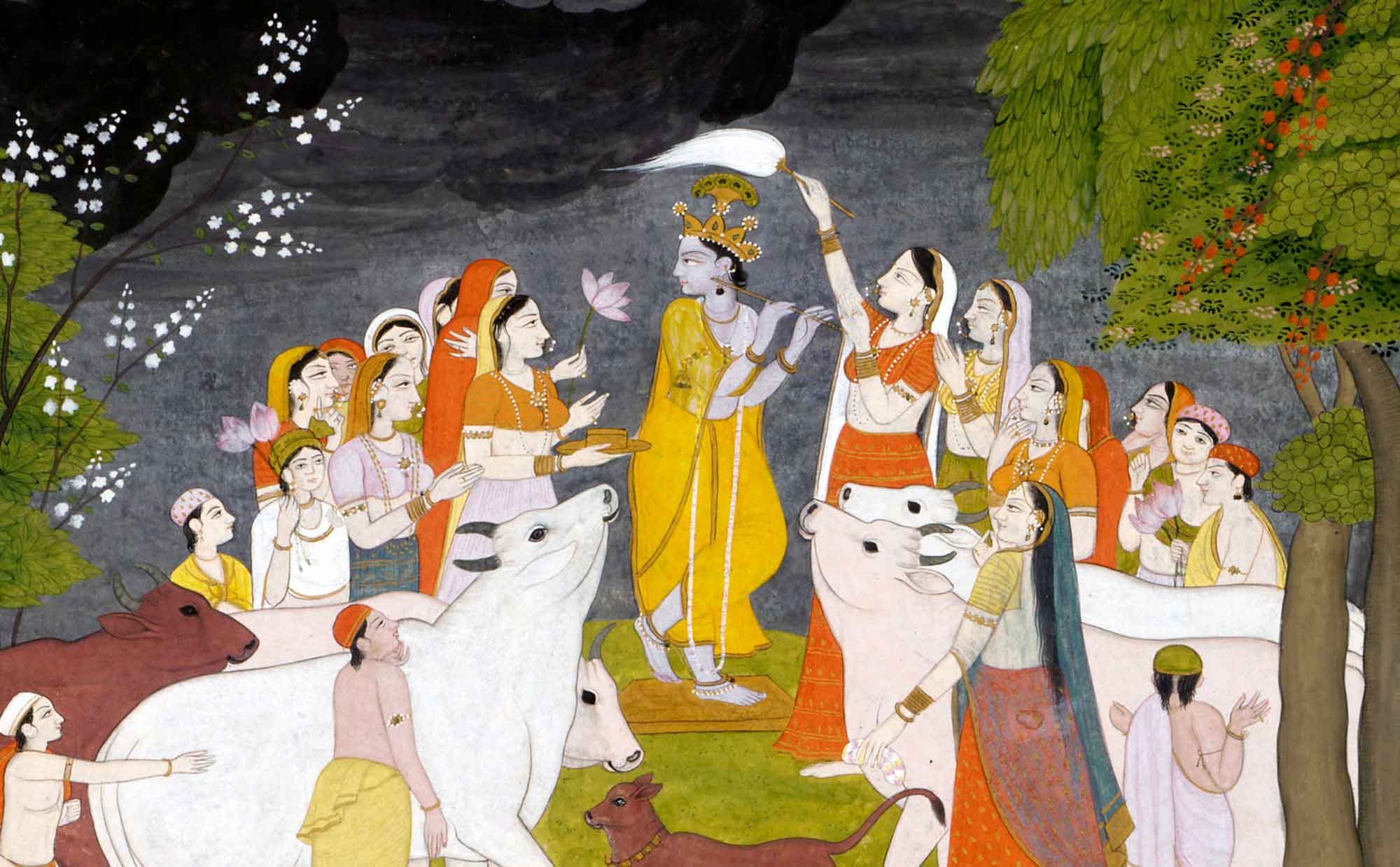

(c) DEVELOPMENT OF AMBICA INTO DURGA

The Pauranic age of India followed closely upon the terrible revolution effected on the plains of Kurukshetra. It was an age of love, not of hatred, on age of illustration, not of originality, and it sought to amplify the crude revelations of the Vedas, so as to suit the same to all sections and communities of a diversified nationality; and Ambica was shewn in different forms, now with four hands, bestowing upon man the four requisites, virtue, wealth, enjoyment and salvation; now with ten, representing the ten principal deities as Dasa-Dik-palas, the preservers of the ten directions beginning with Indra, the most brilliant of the Vedic gods. And we find Her also surrounded with a number of minor deities, representing the full force of the Vedic sacrifice. While also the kingly class were glad that the same Ambica had made common cause with their heroic forefathers, and fought battles on their behalf. Such a representative, all-powerful, all-comprehensive deity, Durga, was worshipped for the first time by King Suratha of the lunar dynasty. And so, She came to be loved, adored and worshipped as the foremost popular Deity and in deversified ways, esoteric and exoteric, subjective and objective, rational and irrational. But the true spirit pf the Vedic remained intact; in other words, the propriety of a feminine mediation between man and God, the necessity of a divine maternal agency for human deliverance, the worship of God as Mother in fact, was never lost sight of.

(c) DIVINE WISDOM OF DURGA

Max Muller finds it difficult to reconcile his theory of the non-Vedic, non-Aryan origin of Durga with undubitable Sastric testimony that Durga was the “representative of the Divine Wisdom.” He refers to the Kena-Upanishad — [we have already quoted the passage (p. 75, Vol. V.)] and remarks that “as early as the time of the Kena-Upanishad, the knowledge of the true Brahma is embodied in a being called Uma-Haimavati. She is also called Ambica, Mother, Parvati, living in the mountains, and her husband is identified with Rudra (Taitt. Ar.18)” Now we have shown, as clearly as we could that Durga represents Agni, whence Her Vedic origin. Agni was known to the Rishis of the Vedas as medhabi (having medha or intelligence). They declare Him residing in the Sun, as will appear from l-2-10 Sama-veda,

oṁ ādit pratnasya retaso jyotiḥ paśyanti vāsaram Iparo yadidhyatī divi II

“As this Agni shines in the sky, men see the sun, in whom the eternal Indra resides.”

Chhandogya Upanishad says,

asau vāva loko gautamāgnis tasyāditya eva samid

raśmayo dhūmo hararciś candramā aṅgārā nakṣatrāṇi visphuliṅgāḥ Iparjjanyaḥ – pṛthivī – puruṣaḥ – yoṣā vāva gautamāgniriti II

“O Goutama, the universal Agni has the Sun as His samit (fuel), the Rays as His smoke, the day as His brilliance, the moon as His charcoal, and the stars as His sparks. The cloud, the earth, the man, the woman, are all but manifestations of Him.”

Agni is, therefore, according to the Vedas, an intelligent Being that illumines the Sun, in whom Indra, the commander of the clouds resides; and in whom is the Earth again, with Her men and women. When Durga represents that Agni, we may very well understand Her as the highest divine wisdom incarnate conceivable.

Agni was the most ancient of the Aryan gods. Scholars are of opinion that some Vedic names of Agni such as Yabishtha, Pramantha, Bharanyu and Ulka, were borrowed by the Western Aryans, and worshipped as Hephaistos, Prometheus, and Pheroneus by the Greeks, as VuIcanus and Ignis by the Romans, and as Ogni the Sclavonians, for thousands of years. But when Buddha put out the sacrificial fire in India, the Greeks, the Romans, the Germans all of them did the same under Christ. Now that a revival of ancient sacrifices has taken place in India with God-Mother as Mediator between Father and Son, the time may come, when our Western brothers will see that it is neither the Father, nor the Son, but the Mother only that presides over and arranges for the world’s responsible household.

(This English article ‘On Durga, Siva and Kali in Their Exoteric Aspects: A Criticism on Max Muller’ by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura appeared in three parts in The Dawn, Vol.2. No. 5, 6 and 8, September/October/December, 1901. There is an older version of this article that he wrote in response to the Anti-Hindu article published in the magazine of the Christian Tract Society in 1899, entitled The Hindu Idols.)